Monsters fascinate. There’s something in the shadows that you don’t understand, can’t quite make out the shape of—something that can eat you. Something that can steal your children, spoil your crops, or worst of all turn you into a monster yourself, so that you’ll no longer be welcome in the warm places where we tell stories about monsters.

That warm place started as a small campfire in the dark night, surrounded by very real predators. Beside that fire, you could lay down your spear and basket and feel almost safe for the night. We keep fearing monsters even as the shadows retreat and the campfires grow, even now when light pollution banishes them to the few remaining dark corners, where they must surely shiver and tell stories about our advance.

Mustn’t they?

It’s become increasingly obvious that humans are terrifying. Not only in the “we have met the enemy and he is us” sense, but in the sense that we can eat everything, steal offspring, spoil crops, and reshape the world into our image. I had this in mind as I wrote Winter Tide—the most sympathetic species can be terrifying if you catch their attention, and the people who terrify you may huddle around their own campfire.

Sometimes I want to hide in the shadows near that campfire, and listen to the stories.

Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley

Shelley’s masterpiece is as famous as a book can get, and as misunderstood as its non-titular main character. Thinkpieces invoke it as a warning against scientific hubris. In fact, it’s a fable about the importance of good parenting: Dr. Frankenstein brings his revenant into the world, and promptly abandons him in a fit of revulsion. That leaves the unnamed monster to wax philosophical, teach himself to read, and make tentative forays into joining human society. Unfortunately for him, humans tend to run screaming at the sight of sewn-together corpse quilts. Or sometimes they just attack. Eventually, he decides we’re not worth having around.

Shelley’s masterpiece is as famous as a book can get, and as misunderstood as its non-titular main character. Thinkpieces invoke it as a warning against scientific hubris. In fact, it’s a fable about the importance of good parenting: Dr. Frankenstein brings his revenant into the world, and promptly abandons him in a fit of revulsion. That leaves the unnamed monster to wax philosophical, teach himself to read, and make tentative forays into joining human society. Unfortunately for him, humans tend to run screaming at the sight of sewn-together corpse quilts. Or sometimes they just attack. Eventually, he decides we’re not worth having around.

If at any point in the book, Dr. Frankenstein could have gotten his act together enough to love his kid, this would be one of those stories about an ugly duckling finding his place. Instead it’s a perfect tragedy about how monsters are born not out of the inherent hubris of their creation, but out of our own fears.

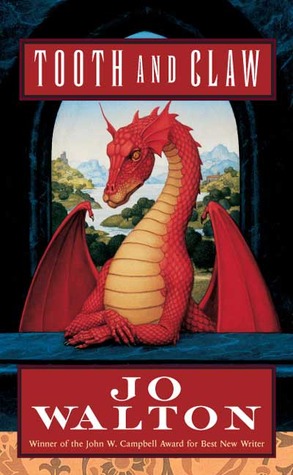

Tooth and Claw, by Jo Walton

Tooth and Claw is a Victorian novel of manners. It starts with a fight over inheritance, and concerns itself with forbidden romance and ambitious merchants and social welfare movements. Oh, yes, and all the characters are cannibalistic dragons. The inheritance fight is over who gets to eat which parts of the family’s deceased patriarch, thereby gaining the magical power and strength of his flesh. The social welfare movement may be radical, but would certainly never forbid the rich feeding their offspring a nutritious diet of “excess” poor children.

Tooth and Claw is a Victorian novel of manners. It starts with a fight over inheritance, and concerns itself with forbidden romance and ambitious merchants and social welfare movements. Oh, yes, and all the characters are cannibalistic dragons. The inheritance fight is over who gets to eat which parts of the family’s deceased patriarch, thereby gaining the magical power and strength of his flesh. The social welfare movement may be radical, but would certainly never forbid the rich feeding their offspring a nutritious diet of “excess” poor children.

It’s a wicked and witty commentary on the ostensibly bloodless conflicts of Trollope and Austen. The monsters, even as they cheerfully consume their own kind, make for remarkably good company. I’d happily join them for afternoon tea—as long as I was very sure of the menu in advance.

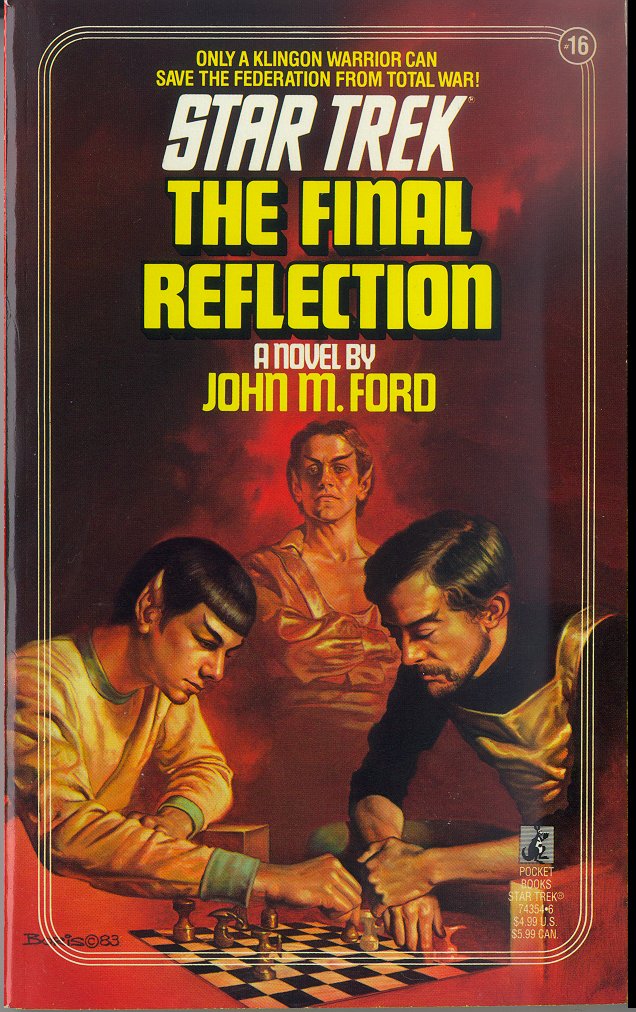

The Final Reflection, by John M. Ford

Klingons have gotten pretty sympathetic in the past couple of decades. In the original series, though, they were the most two-dimensional of goateed villains. The Final Reflection was the first story to give them a rich and detailed culture, to give them nuance while still letting them be worthy antagonists to the Federation. Ford’s Klingons keep slaves, merge chess with the Hunger Games for their national sport, and see conquest as a moral imperative. (That which does not grow dies, after all.) They also love their kids, and draw real and deep philosophy from their games of klin zha kinta.

Klingons have gotten pretty sympathetic in the past couple of decades. In the original series, though, they were the most two-dimensional of goateed villains. The Final Reflection was the first story to give them a rich and detailed culture, to give them nuance while still letting them be worthy antagonists to the Federation. Ford’s Klingons keep slaves, merge chess with the Hunger Games for their national sport, and see conquest as a moral imperative. (That which does not grow dies, after all.) They also love their kids, and draw real and deep philosophy from their games of klin zha kinta.

Reflection reveals the truth behind the mustache-twirling not only to 20th and 21st century readers, but to the 24th century as well. In the framing story Kirk is alarmed to come back from leave and find his crew passing around surreptitious copies, swearing in klingonaase. Krenn’s story is banned by the Federation, of course. Letting people see the monster’s side of the story is dangerous.

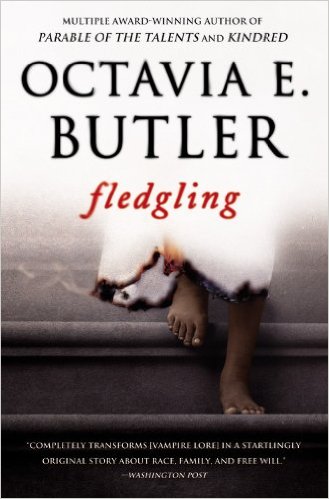

Fledgling, by Octavia Butler

I’m a hard sell on vampires, and an almost impossible sell on amnesia stories. But I adore beyond words Butler’s final novel, the tale of a young woman who wakes up with no memory—and turns out not to be as young as she looks. Like most of Butler’s work, it dives deep into questions of power and consent. Shori has to drink blood to live, and can’t help forming an intimate and unequal bond with those she feeds from. In between trying to learn who stole her memory and why, she has to figure out how to have an ethical relationship with people inherently weaker than her—and whether it’s even possible.

I’m a hard sell on vampires, and an almost impossible sell on amnesia stories. But I adore beyond words Butler’s final novel, the tale of a young woman who wakes up with no memory—and turns out not to be as young as she looks. Like most of Butler’s work, it dives deep into questions of power and consent. Shori has to drink blood to live, and can’t help forming an intimate and unequal bond with those she feeds from. In between trying to learn who stole her memory and why, she has to figure out how to have an ethical relationship with people inherently weaker than her—and whether it’s even possible.

There were supposed to be more of these, damn it.

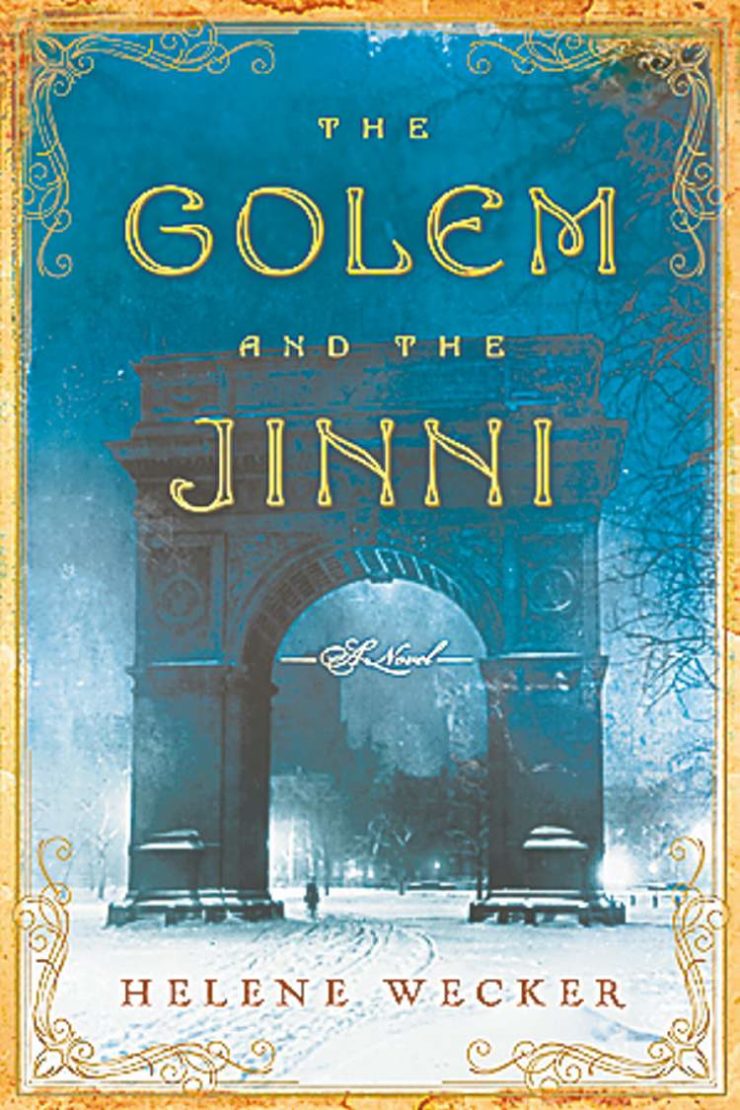

The Golem and the Jinni, by Helene Wecker

I mmigrants come to the US and try to fit in—learn the language, get a job, find friends. Wecker’s protagonists are no different, except that they happen to be a fire elemental locked in human form by unknown magic, and a golem whose master died shortly after awakening her in the middle of the Atlantic. Ahmad is arrogant and impetuous, a monster because of his confident lack of concern with others’ needs. Chava is made to put others’ needs first, but still a monster because—as everyone knows—all golems eventually run mad and use their inhuman strength to rend and kill until they’re stopped.

mmigrants come to the US and try to fit in—learn the language, get a job, find friends. Wecker’s protagonists are no different, except that they happen to be a fire elemental locked in human form by unknown magic, and a golem whose master died shortly after awakening her in the middle of the Atlantic. Ahmad is arrogant and impetuous, a monster because of his confident lack of concern with others’ needs. Chava is made to put others’ needs first, but still a monster because—as everyone knows—all golems eventually run mad and use their inhuman strength to rend and kill until they’re stopped.

Together, they don’t fight crime (mostly), but they do help each other resolve the mysteries behind their respective creations. They compliment each others’ strengths and monstrous natures. Chava teaches Ahmad how to take care of people beyond himself, and Ahmad helps Chava learn to value herself. They give each other the thing Frankenstein’s monster never had, and together find a place in the world and a community where they can survive.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is available from Tor.com Publishing on April 4th. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and her blog, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is available from Tor.com Publishing on April 4th. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and her blog, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.